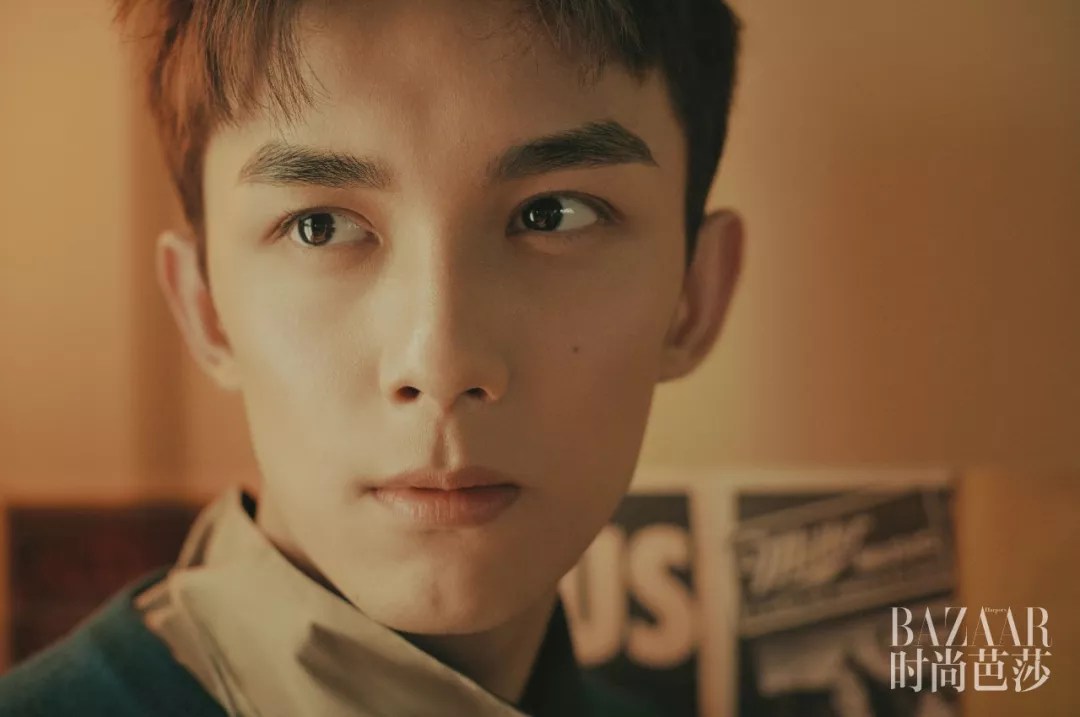

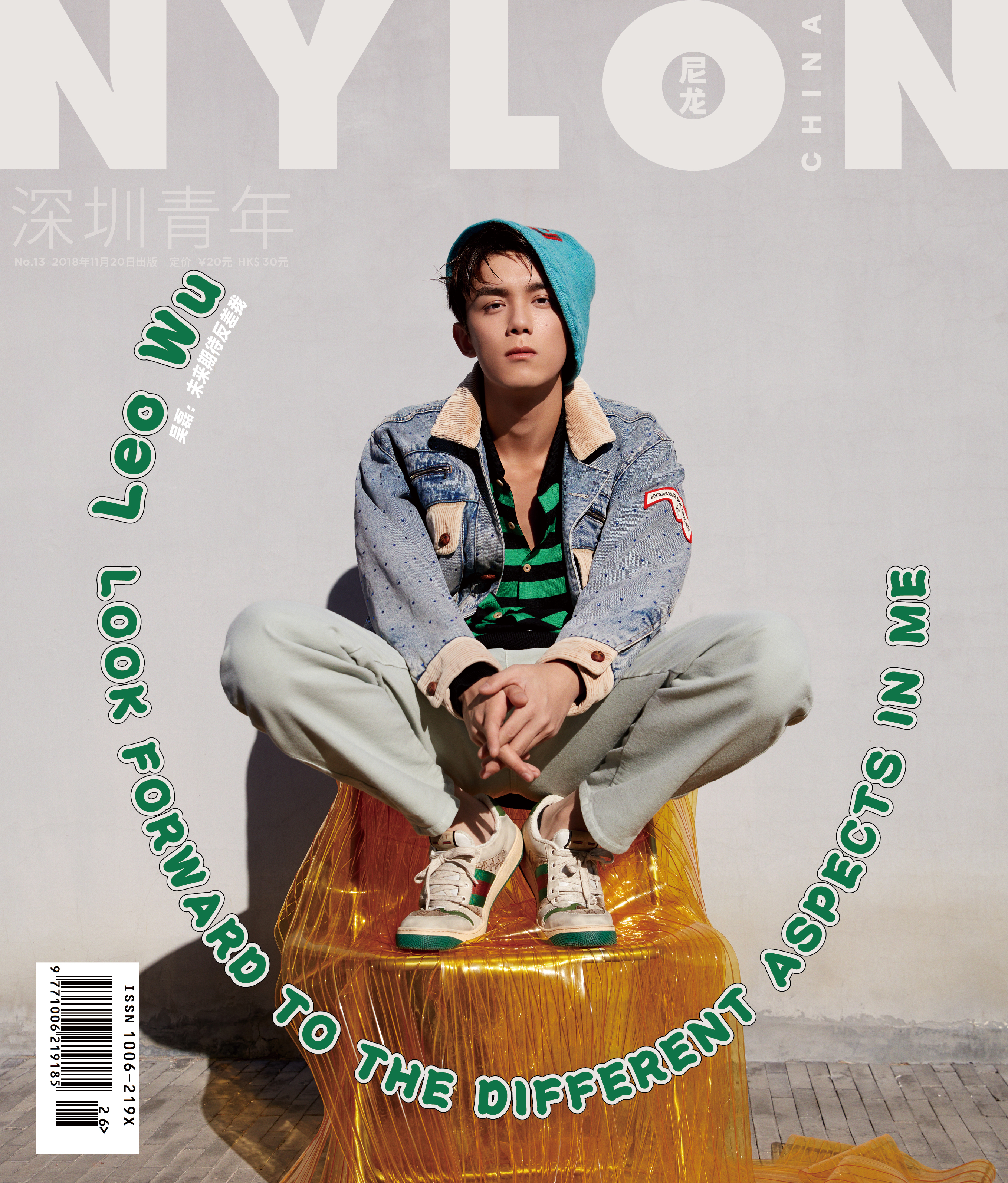

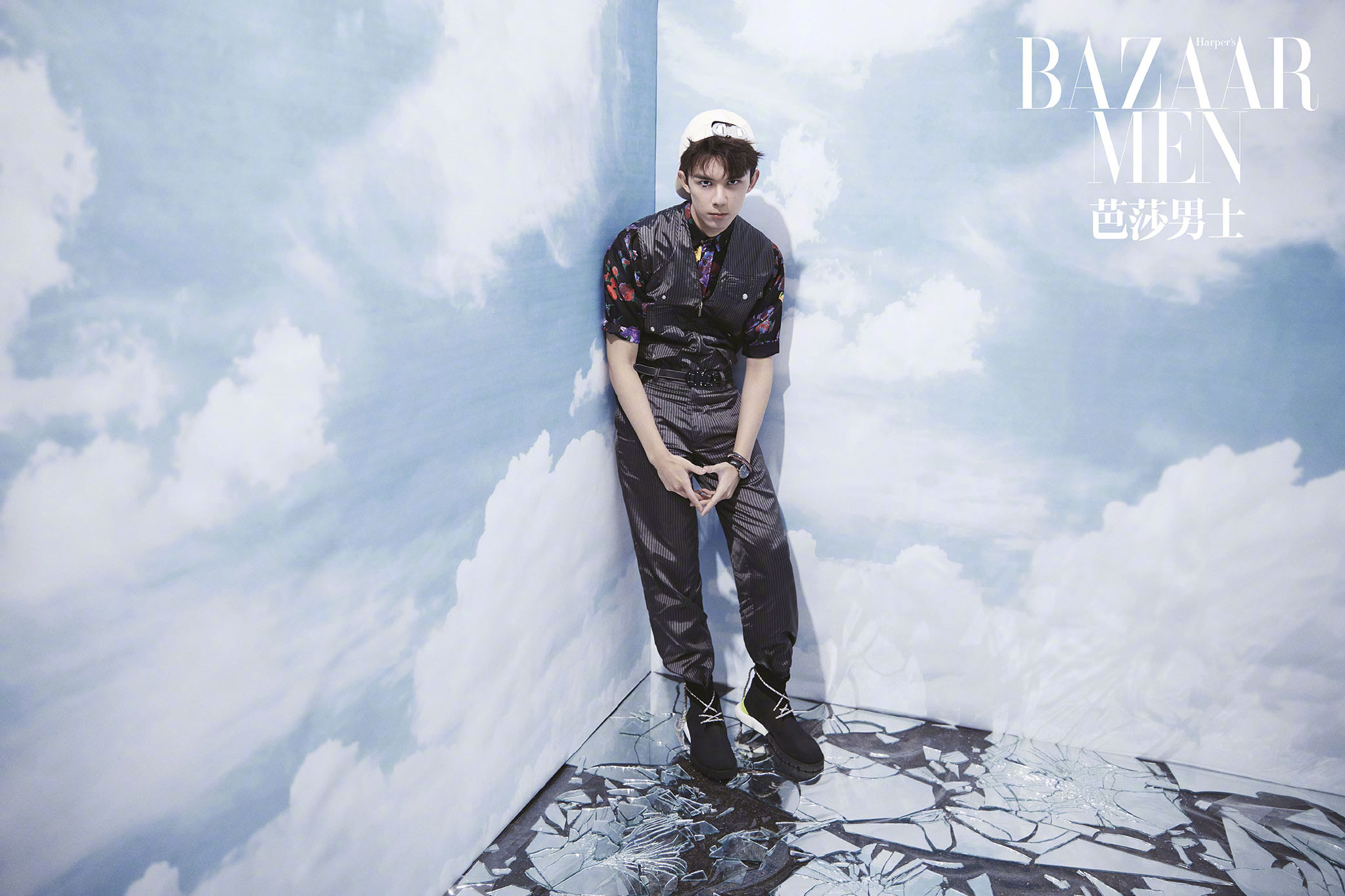

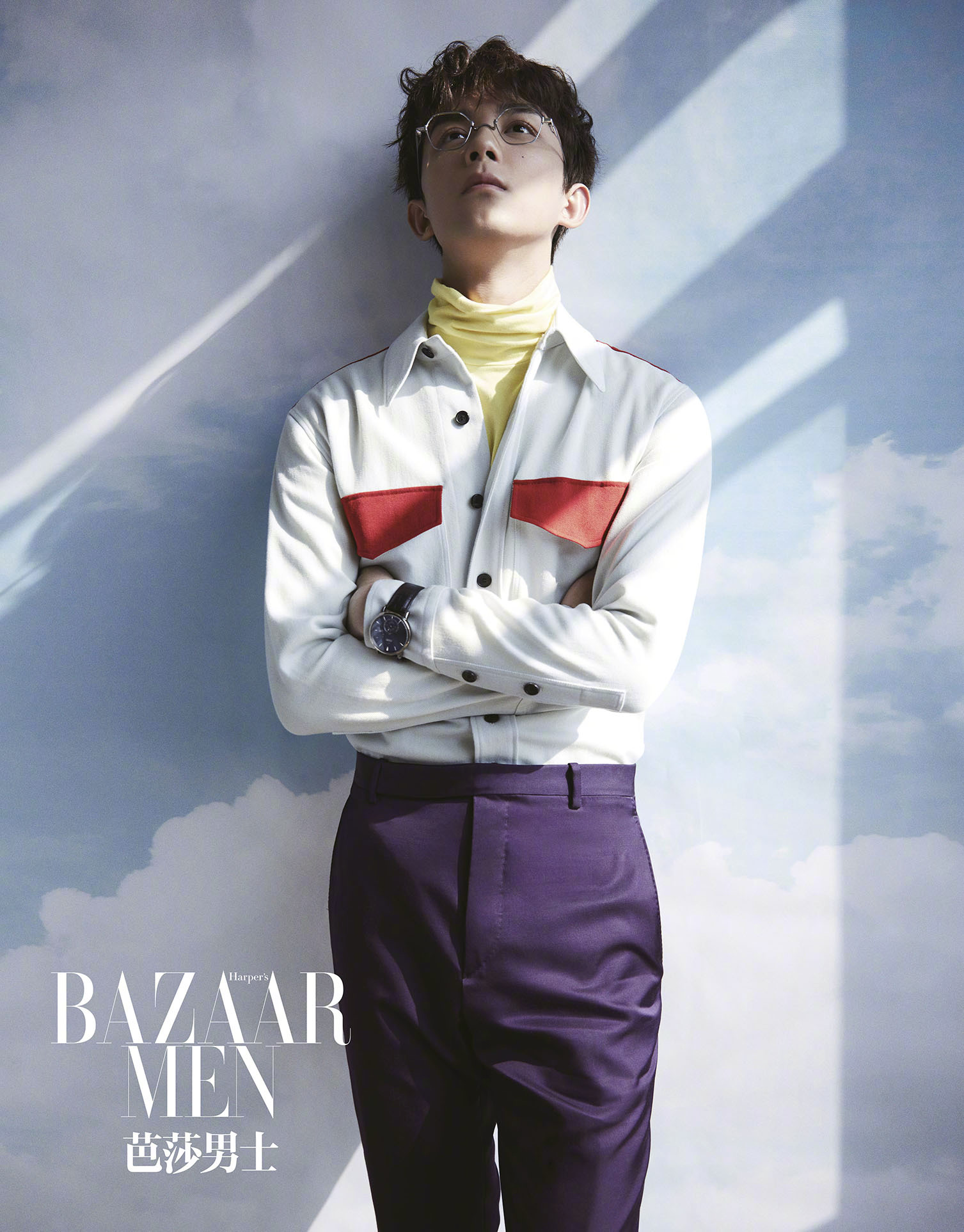

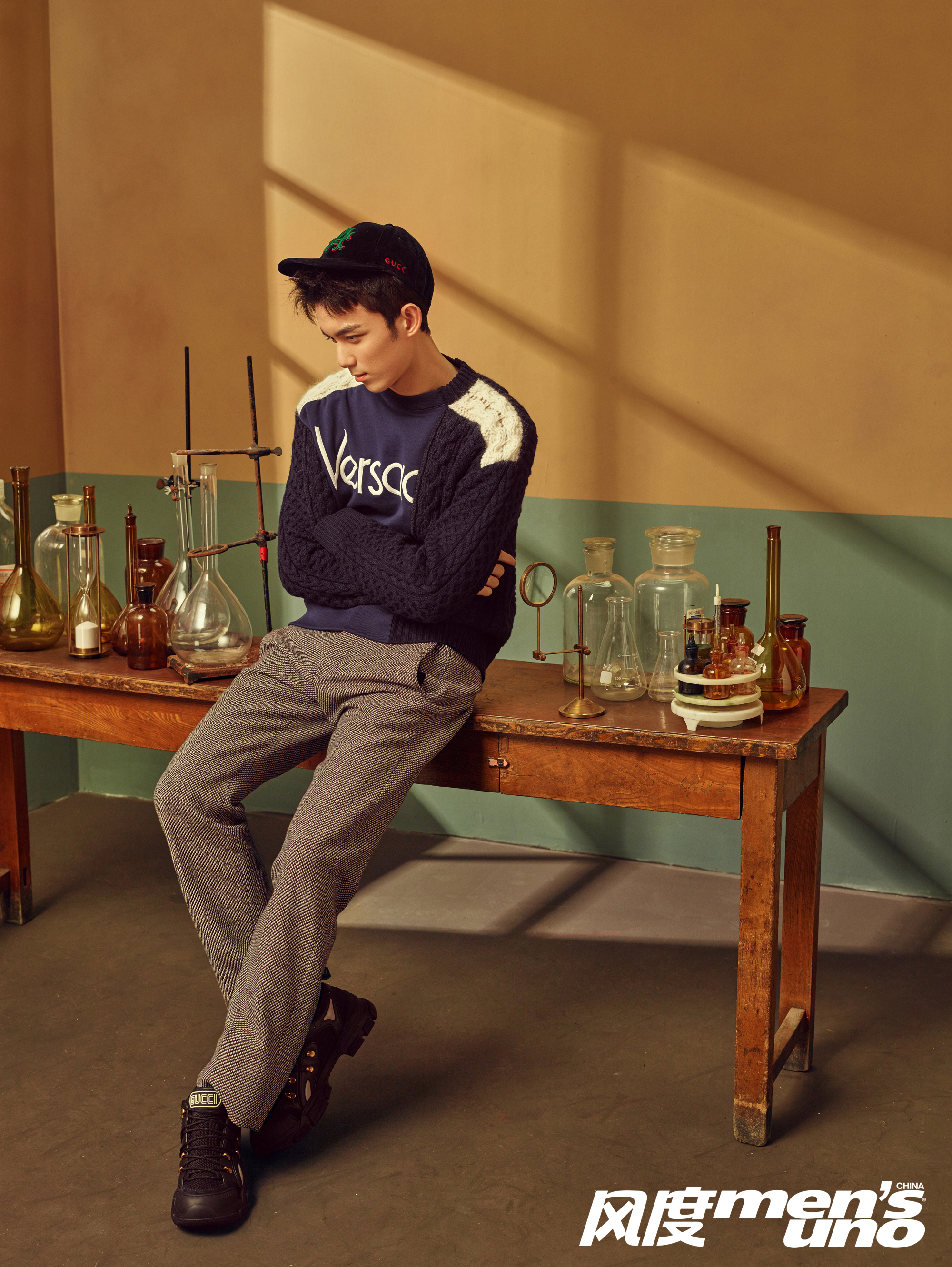

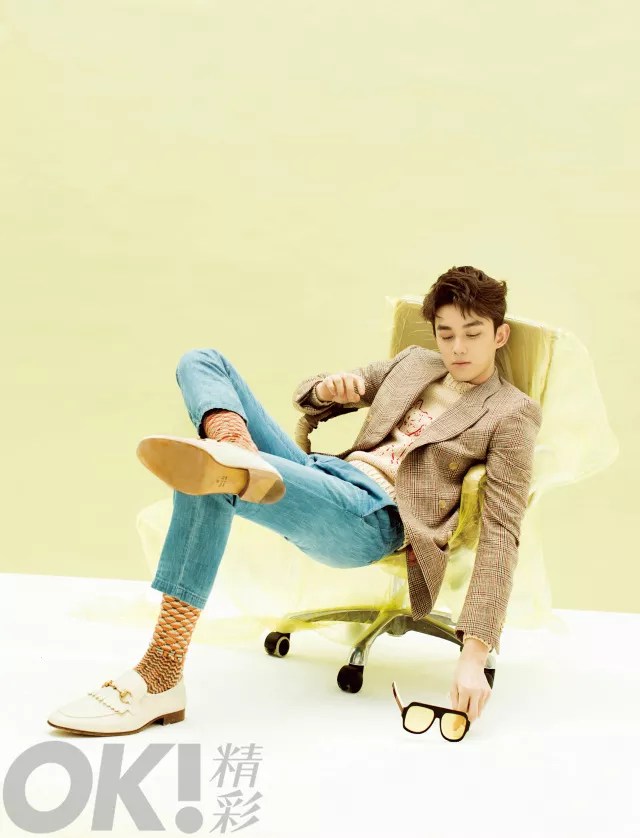

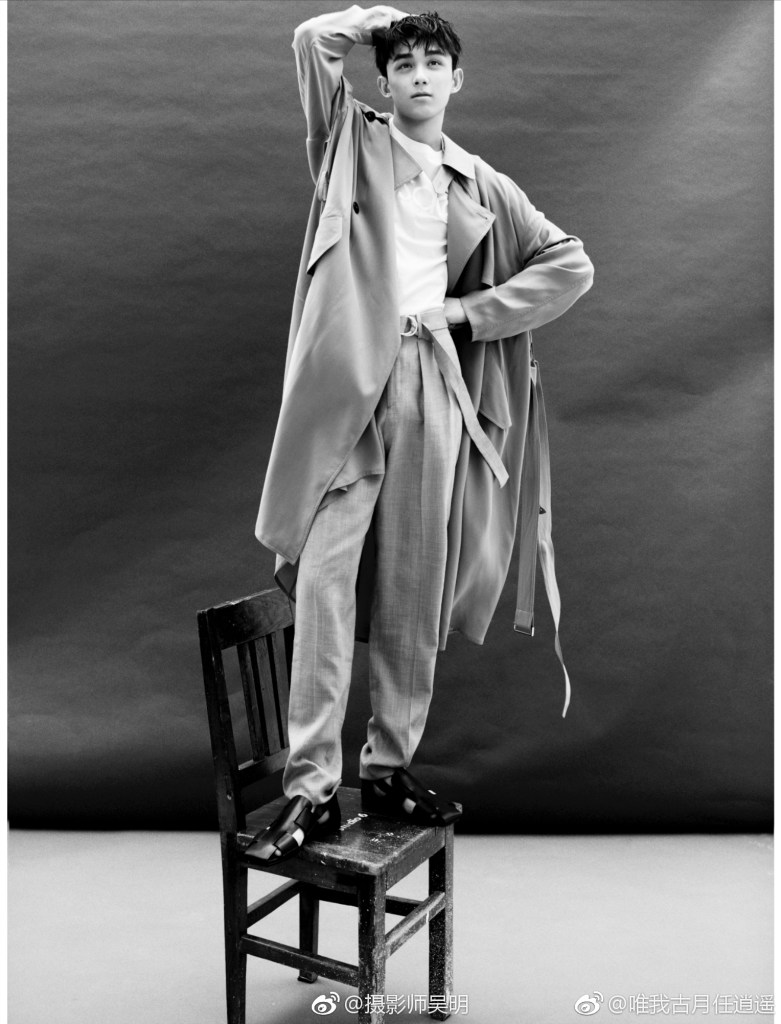

Wu Lei: On the Road

“We must go, and never stop before arriving.”

— Jack Kerouac, On the Road

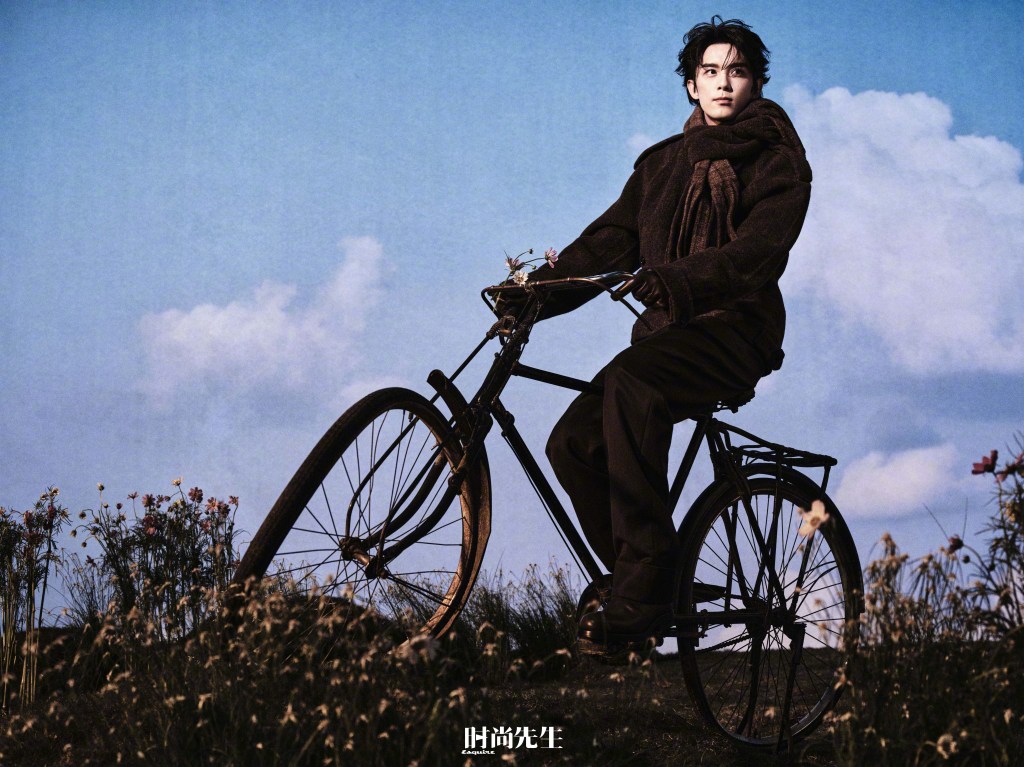

Anyone who has watched Ride Now would find it hard to forget these scenes: By the shores of Sailimu Lake, between the grassland and snow mountains, Wu Lei rides the bicycle alone on the road. First, gritting his teeth through uphill struggles, then reveling in the exhilaration of downhill ride. Wind, rain, scorching sun, hail arrive unexpectedly; his face exposed to the nature, his sunburn and stubble clearly visible. Occasionally, he meets fellow travelers, sitting by the roadside to chat briefly, exchanging contact details before parting ways. More often, it’s cars passing by, phones held out from windows accompanied by a cheerful “Hi!” He simply smiles and responds, “Go quickly.” Then he continues pedaling, sweating, challenging his physical limits.

It’s an unpolished state: wild, natural, genuine, like the most primal existence. One person, one bike, one road, and boundless scenery. Wu Lei says that when he’s cycling, it’s just him alone, he does not overthink miscellaneous things. “It’s a chance to have a conversation with myself and explore more places along the way.”

This, perhaps, is Wu Lei’s “on the road.”

Physically on the Road

Wu Lei’s “on the road” is, first and foremost, a physical exploration.

Cycling is the most direct form of exploration. In the first season of Ride Now, he journeyed to the snow plains of Ulan Butong; in the second season, the vast Sailimu Lake in northern Xinjiang; and in the third season, he reached the volcano crater in Vanuatu. His reasons for choosing these places are simple and straightforward: beauty, vastness, and the unknown. He often saves numerous travel and cycling videos, as if drawing an unfinished map in his mind, and then uses his body to fulfill it step by step

So direct, so clear. Initially, he cycled alone, but later decided to share the process with the world. After the show aired, it almost instantly attracted massive attention. It’s rare to see a star display such a wild side. One viewer commented: “He traversed snow plains, rode horses to chase herds, experienced starry skies and sunrises, and still said ‘it’s okay’. He lives out the youthful dreams in extreme environments.”

During the 90-kilometer ride around Sailimu Lake, Wu Lei encountered almost every type of weather in just two short days: clear skies, strong winds, torrential rain, hail. He did not retreat but pushed forward. Through the camera lens, audiences could directly feel the chill and tension of those moments. “At the time, I felt my physical strength was sufficient, and the road conditions were manageable, so I wanted to challenge myself and persevered,” he said. In his eyes, extreme weather is not an obstacle but rather an experience gifted by the journey.

In his latest film Dongji Rescue, his body was pushed to another extreme—free diving. He joined the crew two months early for training. The film contains extensive underwater scenes, all shot in real environments without the use of a stunt double. Director Guan Hu noted in an interview, “Underwater practical shooting is the most difficult technique,” highlighting the immense challenge for the actor.

Wu Lei, who initially held a deep-seated fear of the ocean, trained his breath-holding to its limits. From basic movements to deep-water pressure adaptation, he gradually tamed his heartbeat and breathing. He says free diving is much like acting: “Both require finding your limits within extreme relaxation.” Underwater, he had to portray his character A-Dang’s intimate connection with the sea. “During the underwater shoots, everyone was challenging their own limits, but for the performance, I had to fully give my body and mind to the character.”

In the film, he rescues people at sea, swimming from a small boat to a warship. When trapped in the prisoner hold as the Lisbon Maru is sinking, he dives into the depths of the vessel, searching for an escape. As damaged parts of the ship collapse around him, he evades them, his body moving with fish-like agility. Under the sea, he and his character, A Dang, dived into the camera, and also into the depths of life.

After wrapping Dongji Rescue, Wu Lei took some time off. He didn’t come to a full stop but continued to pursue movement. He obtained his diving certification, treating the training as a form of “graduation.” He wanted to try skydiving, though it didn’t happen, his eyes still gleamed with a desire “to fly.” On his days off, he also learn a little bit about tea culture. Wu Lei says, “When I have the chance to rest, if something comes to mind, I just go and do it.” For him, the body must move first before the heart could truly arrive.

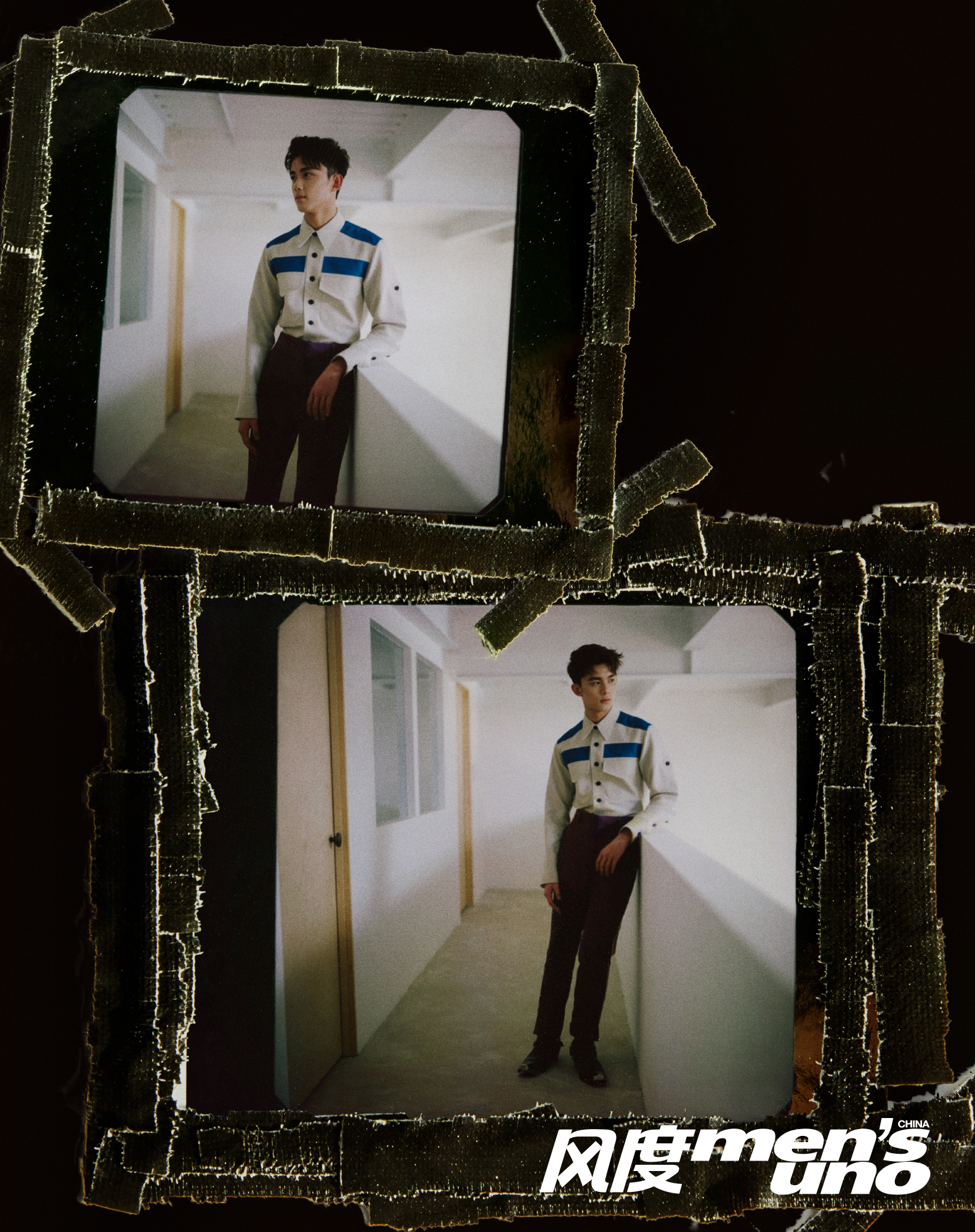

Characters on the Road

Wu Lei is an actor the audience has watched grow up. From the clever and alert young Fei Liu in Nirvana in Fire to the free-spirited and courageous Ashile Sun in The Long Ballad, a generation of viewers has witnessed his growth. Yet, in his own eyes, the more important thing is that each role is a new journey.

Dongji Rescue brought him to an unfamiliar place. The crew filmed in a remote village. At the first costume fitting, seeing his tanned skin and bare shoulders, he felt almost shy and could hardly believe it was himself. “I’ve rarely filming in such scanty clothing, but gradually, I got used to it.” In the film, his character A Dang is an outcast on the island. He and his brother, descendants of pirates, were once homeless. After being rescued, the two brothers faced rejection and lived independently on the far side of the island, fishing for a living and keeping apart from the villagers.

Yet A Dang has retained his innocence and kindness. Whenever there is trouble at sea, he rushes to help. When he sees someone drowning, he doesn’t ask where they’re from. His instinct simply tells him, “I must save them.” This is where the story begins.

To fully embody A Dang, Wu Lei crafted a detailed backstory for the character himself: his life story of being adopted as a child, the sense of duty he carries for his older brother, the self-tattooed patterns on his skin… These details, though never written into the script, became a silent dialogue between the actor and the role.

One scene that left a deep impression on him was set inside the prisoner-of-war hold. Entering the 1:1 replica of the space, dark, enclosed, and suffocating, he saw prisoners crammed like sardines in can beneath wooden beams and canvas, facing imminent death. The overwhelming sense of oppression and discomfort stirred in him a visceral connection to the past. He reflected on the tragic yet courageous real-life fishermen who risked gunfire to rescue British POWs (prisoner of war). “I hope this part of history becomes known to more people,” he said.

In another scene by the sea, after a British POW goes missing, Japanese troops arrive on the island threatening to massacre everyone unless the prisoner is handed over. Soon after, several villagers are killed. During filming, Wu Lei found it difficult to contain his anger. “Just recreating the scenes of that era through acting is already heartbreaking. I can’t help but think about the suffering our ancestors endured.” This emotion reshapes the performance and allows the character to tap into the essence of life.

For Wu Lei, acting is not about fulfilling a task. It is yet another form of being “on the road”: opening a new door, stepping into an unfamiliar world, and ultimately emerging transformed.

Mentality on the road

Whether it’s cycling or acting, Wu Lei’s key theme has always been “on the road.” Yet for him, this phrase signifies more than a romantic ideal of distant journeys. It reflects a simpler, more grounded choice: to live fully in the present, to cherish each moment, and to seek eternal strength in them.

Although he is now widely known for his love of cycling, he doesn’t force himself to stick with it indefinitely. “Maybe I love cycling now, but one day if I don’t, I’ll stop riding and find the next sport or hobby I enjoy. I won’t push myself to persist, but I also won’t stop moving.”

In Ride Now, he is not only the cyclist but also the director, cinematographer, planner, and one-person crew. He lets the camera capture reality, speaking when he feels like it, staying silent when he doesn’t. He captures his true self, his genuine vulnerability, but also the excitement and joy the journey brings. For example, after completing the loop around Sailimu Lake, he returned to retrieve a large stone he had placed at the starting point. Nestled in a circle of green grass, the stone lay quietly, waiting for him. He picked it up and captured that moment. “Because that,” he says, “is who I am at this very moment.”

If A Dang from Dongji Rescue and Wu Lei from Ride Now were placed in the same frame, what would they say to each other?

Wu Lei’s answer was simple: perhaps they wouldn’t say much at all. A single look would be enough.

“Come on, let me show you my treasure.”

“Yeah, let’s go and see my world.”

Finally, we asked him: What does “being on the road” mean to you?

His answer was brief yet moving:

“It’s every moment right now. I’m breathing, feeling the air of a new day. That’s me, on the road.”

Q&A

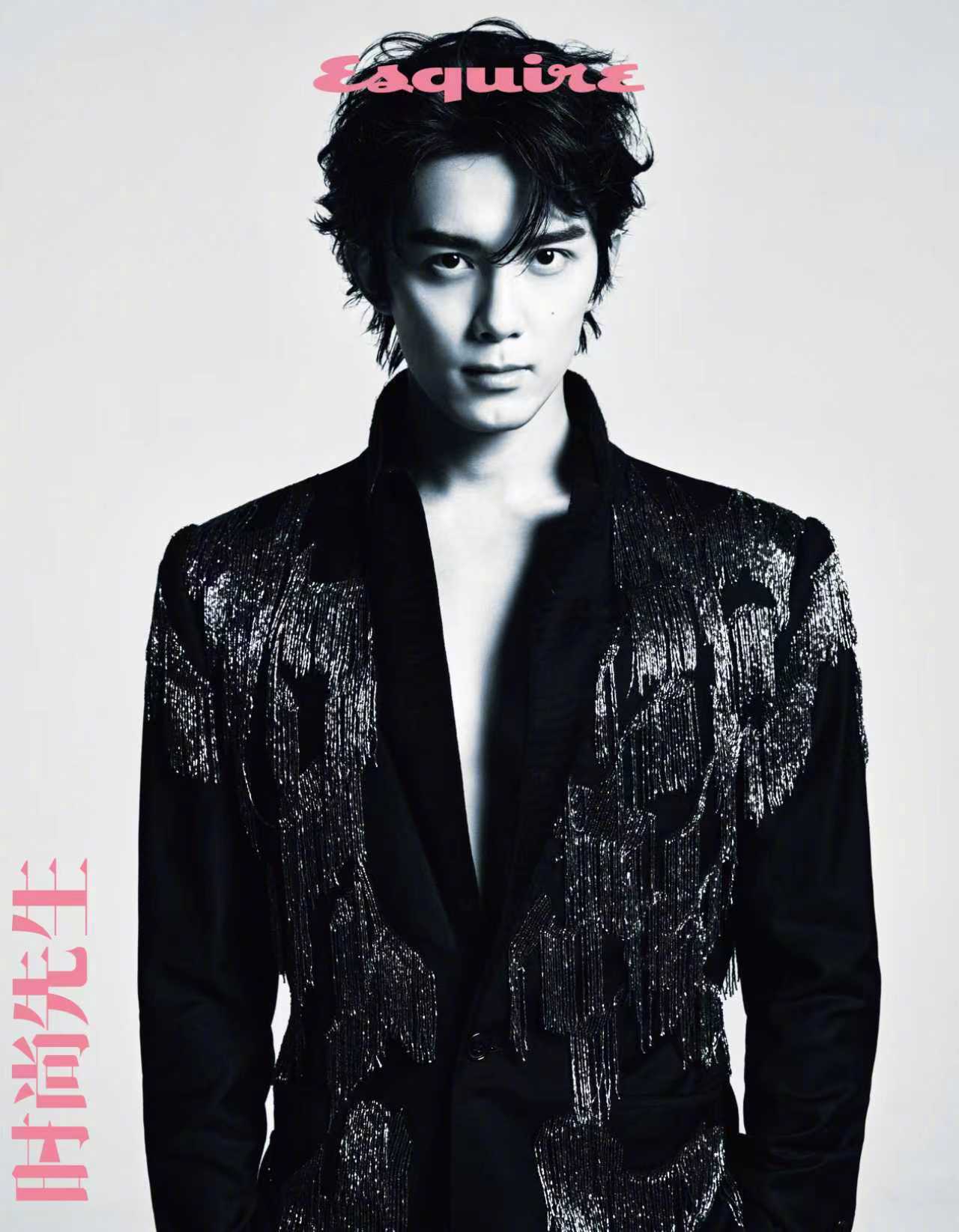

Esquire: When you first learned about Dongji Rescue, a project based on the true story of a sea rescue, what made you immediately decide to take on the role of A Dang, the fisherman?

Wu Lei: From the moment I read the script, I was deeply moved by the story. I also found in A Dang a character with ample room for creative interpretation. A role I felt strongly drawn to. I wrote a personal backstory for him: how he was found and adopted as a child, the tattoos I imagined he gave himself after seeing his older brother being bullied because he felt he needed to shoulder something for his brother. There were many small details like these. Later, through discussions with both directors and our crew, we gradually made A Dang more complete and richly layered. That entire process brought me a lot of joy.

Esquire: During the costume fitting, we heard that when you first saw your look in the film, you could hardly believe it was yourself. From feeling a bit shy to fully embracing the image, what kind of mental adjustment did you go through?

Wu Lei: For the sake of the film and the character, there’s nothing I can’t accept. At the beginning, it was indeed uncomfortable, I rarely shoot wearing so little but gradually I got used to it.

Esquire: We heard you originally had a fear of deep sea, yet pushed yourself to train until you could hold your breath for a long time. Could you talk more about that training process? Was there a moment when you first felt, “I might actually be able to do this”? You mentioned that “free diving is a lot like acting, both require finding your limits within extreme relaxation.” During the underwater filming, what did that “limit” specifically refer to?

Wu Lei: During my first training session, the coach explained a lot of theoretical knowledge about free diving and tested my basic abilities. Step by step, I was taught the correct breathing techniques, swimming postures, and gradually moved on to descending and ascending in deep water, maintaining neutral buoyancy, and finding balance underwater. Only after I gained a certain level of control over deep-water free diving, we began specialized training tailored to each specific scene, and I slowly started attempting underwater pressure adaptation.

It was a gradual process. Every day, I found small successes and a sense of achievement, which made me think, “I really can push my limits further” and “If I can already do this, then where exactly is my limit?”

During the underwater shoots, everyone was challenging their mental and physical limits. After all, being in deep water isn’t like being on land. The depth and the feeling of losing control can trigger instinctive fear. ach of us has a maximum breath-holding time , and I often saw our underwater cinematographers holding their breath with great effort, their diaphragms cramping continuously. But my character, A Dang, is someone with excellent swimming ability. Underwater, I had to portray his ease and affinity with the sea, giving my body and mind entirely to the performance. That in itself was quite a challenge.

Esquire: In filming Dongji Rescue, what left the deepest impression on you? How would you describe your breakthrough or growth as an actor in this project?

Wu Lei: The scene that left the strongest impression on me was the one where the villagers were killed. While filming, I really struggled to contain my anger. We live in an era of peace so just recreating those moments through performance was deeply painful. I couldn’t stop thinking about what it must have been like for our ancestors who actually lived through those times, the suffering and despair they endured.

Through this film, I experienced long-term, high-intensity underwater shooting for the first time. A completely different way of performing compared to working on land. It also pushed me to successfully learn free diving.

Esquire: We heard that after wrapping Dongji Rescue, you took some time off and spent your days doing various sports. Could you tell us more about that period? For example, you got your professional diving certification and mentioned wanting to try skydiving. Why did you choose to stay active instead of just lying down to rest? Was it a shift in your mindset?

Wu Lei: Having the chance to take some time off was really nice. It gave me a much-needed breather after a long period of filming. As for the diving certification, I’d been wanting to get it for a while but never had the time. Finally having the opportunity felt like a small graduation from all the training. Skydiving is something I’ve wanted to try for a long time, though I haven’t quite mustered the courage yet. Maybe one day, when I suddenly feel ready, I’ll go for it.

It wasn’t all about being active, though. I rested a lot too. When I have downtime, I tend to follow my impulses. If something comes to mind, I just go and do it. For example, during that break, I also learn a little bit about tea culture, though just scratching the surface.

Esquire: You come across as someone with a lot of energy. Beyond acting, you also pursue cycling. We’d love to hear more about how you selected the destinations for Ride Now. From Ulan Butong in the first season, to Northern Xinjiang in the second, and Vanuatu in the third. What made you choose these three places, and which ride made you first think, “I want to share this journey with everyone”?

Wu Lei: I often watch a lot of travel and cycling videos and save places I’d like to visit. Ulan Butong has stunning snow plains, Northern Xinjiang’s Sailimu Lake is incredibly vast, and Vanuatu is one of the few places where you can get up close to an active volcano.

The decision to share was actually quite spontaneous. I had just gotten into cycling and happened to be heading to another city for filming, so I bought some gear on a whim and hit the road. It was also by chance that people responded so positively. There was a lot of feedback and support. That casual sharing gradually evolved into the Ride Now vlog, and it took on a deeper meaning for me.

Esquire: When did you first start cycling, and what do you feel during your rides?

Wu Lei: Cycling helps me relax. During those moments, it’s just me and the road. As long as it’s safe, I don’t overthink miscellaneous things. It’s a chance to have a conversation with myself and explore more places along the way.

Esquire: In the first episode of the Northern Xinjiang chapter, you cycled 90 kilometers alone around Sailimu Lake and suddenly encountered hail. You later said, “Sailimu Lake was quite generous. It let me experience every type of weather in just two days.” It seems even extreme weather feels like a valuable experience to you. Was that the most dangerous situation you’ve faced on a ride? Why did you choose to keep going instead of seeking shelter?

Wu Lei: It wasn’t particularly dangerous, I had a team with me. If I had run out of strength, there would have been people to help me. Everyone should assess their abilities and prioritize safety when encountering extreme weather outdoors.

At the time, I felt my energy was still sufficient and the road conditions were manageable, so I decided to challenge myself and keep going.

Esquire: In this project, you serve simultaneously as the director, writer, and cinematographer. When the lens is turned toward yourself, how do you decide “which vulnerabilities can be left in”? For example, you mentioned that if you don’t feel like speaking, you stay silent. What does cycling mean to you? Is it an escape from your daily life as an actor and public figure, or is it another form of creation?

Wu Lei: Everything can be left in because it’s all part of who I am in that moment. Well, except for the time when I was afraid of little monsters in the water. Now, I think about it, I’m not afraid anymore.

Cycling is a way for me to clear my mind. I might love it now, but if one day I don’t, I’ll stop, and find the next sport or hobby I enjoy. I won’t force myself to persist, but I also won’t stop moving.

Riding is truly a form of rest for me. It takes me out into a bigger world, and along the way, I’m also documenting and growing.

Esquire: If A Dang from Dongji Rescue and Wu Lei from Ride Now were edited into the same scene, what do you think their opening lines would be?

Wu Lei: I don’t think they’d say much at all. Just a look. “Come on, let me show you my treasure.”

“Yeah, let’s go and see my world.”

Esquire: So far, only two episodes of Season 3 have been released. Planning for the rest of the season is already underway. While the route remains a secret, could you reveal one small item you “must bring on the road” and its significance?

Wu Lei: I bring my eyes and my brain. To see and to remember all the scenery.

Esquire: How do you interpret the phrase “on the road”?

Wu Lei: It’s every moment right now. I’m breathing, feeling the air of a new day. That’s me, on the road.

Source: Esquire